Check out Lexi’s testimony of wrestling her culturally liberal sensibilities, her love for LGBT+ people, her desire for consistency, and her surprising conversion.

I am perhaps not the typical candidate for someone whose life would be drastically changed by Equip.

My upbringing was an artsy crossover of liberal Christianity, science fiction writers, and blue-state politics. By 8th grade, I had openly gay school teachers, whom I adored. By 10th grade, homophobia was loudly decried from most spaces I occupied, I had gay friends, and I didn’t see why the big bad conservatives (none of whom I knew personally) were so fussed about what other people did in the privacy of their bedrooms. I shaved my hair off in high school in 2005, long before the style became mainstream among women. My friends and I were proud of being part of what was, at the time, a fringe subculture. So when we started searched for a church that would be a good fit for both of us, my new husband and I were surprised to be drawn to a more liturgical space.

It was even more of a shock when we landed in a buttoned-up yet friendly, conservative Anglican church in 2017. This was the world my fringy, liberal community had always rejected, derided, shuddered at the thought of. Yet my husband and I found much to love in this new setting: sincere, deep faith; genuine hospitality; healthy friendships; mutually supportive, vibrant community; beautiful liturgy; deep and serious theology; an emphasis on humility and personal virtue and celebratory feasting. Many of our closest friendships were formed there. Our lives were dramatically changed for the better, and we are forever indebted to that church.

And yet, I lived in an uneasy tension, unsure how to bridge my old world with my new. It seemed that the more disciplined culture allowed less room for creative expression or open discussion of disagreements. I first heard only whispers about homophobia in our new church setting, rarely a direct mention of the word—something that seemed like it would break an unspoken taboo—but a sort of murmur that I didn’t like. It suggested to me that there was an undercurrent of discomfort, uncertainty, or prejudice toward LGBT+ people. Then I started to hear about more direct comments, injured feelings, and attitudes that my old world had always pushed so hard against.

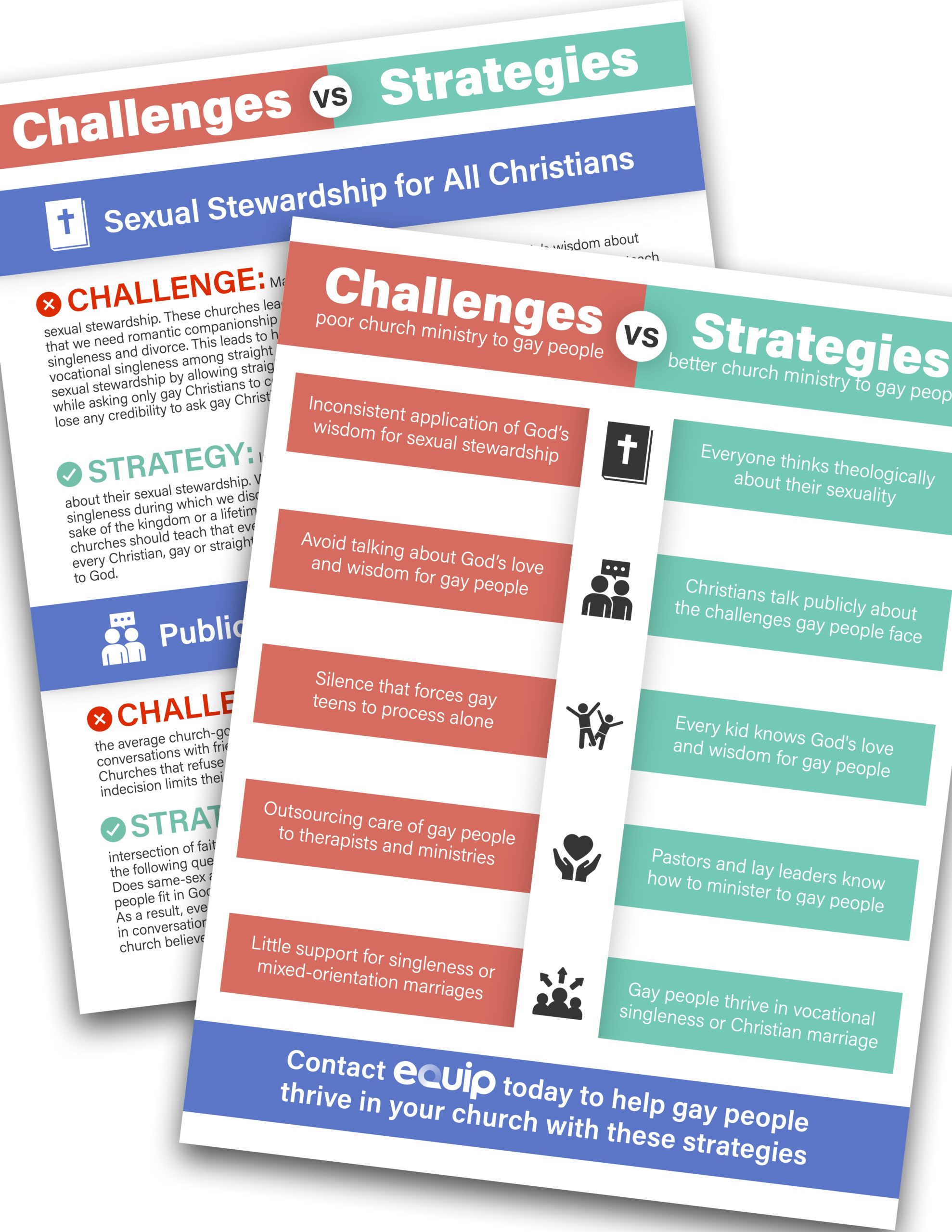

I had tried to set aside my own prejudices and assume the best of people while I explored this conservative church world for myself. Despite the warm-hearted attitude of most of my fellow parishioners and our pastoral staff, it was clear some serious problems persisted in the evangelical movement overall. Ugly comments from a small minority, in the absence of open support from the majority, were enough to push people out with pain and heartache. It was heartbreaking to see that gay friends were being driven away, feeling rejected or unwelcome. I felt sad and confused, unable to make sense of a culture that had so much good to offer, that had given me a great deal, yet seemed to at times fall into the trap of idolizing marriage or making LGBT+ people into scapegoats. That the scapegoating was often for sexual misbehavior that was, frankly, more common among straight couples made it all the worse.

I wondered, multiple times, if I needed to give it up and head back to the liberal church. Was it even possible to live out historic, traditional Christian values in a way that was truly loving? I didn’t think it was worth having the “right” theology if it meant sexual minorities were rejected, sidelined, and otherwise disrespected. I’d left the liberal church because I needed a community with deeper theology, firmer boundaries, and stronger roots than the no-holds-barred, tear-down-the-norms, slightly dysregulated culture I’d come from. Yet I wondered if I had traded that setting for one that inexplicably squelched nonconformity in a way that drove people out—and right back to where I had begun.

I was caught between two inadequate approaches—one that embraced LGBT+ people but lacked theological depth, and another that upheld deep faith but often left LGBT+ people in the cold. I began to wonder, Is anyone else troubled by this? Surely, I couldn’t be the only one.

It turned out there were indeed others asking the same questions.

My first encounter with Equip was at a Boston Fellows event, and the team’s approach was a welcome antidote to the seemingly irreconcilable tension I felt. Equip recognized the Church’s failures and challenged believers to real faithfulness. Something clicked. I finally felt like I wasn’t crazy—that there might really be a way for me to honor both historic theology and LGBT+ people. The tension I had carried for so long began to ease just a bit.

It was through conversations with Pieter that I sniffed out some of the more concrete dynamics at play and began to grapple with the much deeper questions underlying the whole issue—namely, the Bible’s call to chastity for all, not just some. If sex was really reserved for heterosexual marriage, how could Christians ensure it wasn’t just self-serving, fulfilling a personal desire that others were barred from? I had to face my increasingly guilty conscience on issues like contraception. How far was I willing to go in my belief that theological consistency mattered? If I were divorced, would I want and expect my local church to lovingly hold me to the same standards it asked of my LGBT+ brothers and sisters? And if we took the Bible at its word that celibacy was actually a higher calling than marriage, how could my church shift both its attitudes and its practices to better honor single parishioners, gay and straight alike? As I grappled with the cultural and theological conflict I felt, Equip was one of the only voices I felt I could turn to for guidance—a voice crying out in the wilderness of the conservative church, if you will. Equip is the reason I didn’t throw in the towel and return to a more modernized, liberal church tradition.

A confluence of factors in my own faith journey, including the work of Equip, ultimately led me to the Catholic church. Yet while the Catholic church is more theologically aligned with Equip’s work than most Protestant churches (at least on paper), the reality on the ground leaves much to be desired. For example, while holy orders offer a clear role for some celibate Catholic believers, marriage is still treated as the default vocation, and I’ve yet to hear a single teaching about universal calls to chastity for a general audience. On a personal level, when I share about my own faith journey in Catholic circles, I have to take a deep breath before mentioning contraception and divorce—because in any given group of Catholics, beliefs about the official teachings can range widely. At one point I blurted out something about how marriage doesn’t automatically make a person chaste—and I was met with frozen, confused looks from fellow Catholics, leading me to conclude that the Catholic church also desperately needs deeper teachings on sexuality.

And so, I continue to return to Equip’s resources and wrestlings as these issues rear their heads in my new church context—and I continue to feel immense relief and respect that the Equip team and others are carving out a different, narrow way in our current time. I am immensely thankful to the Equip team for showing people like me that there is a way to befriend, honor, and love our LGBT+ brothers and sisters in the context of a community that calls us all to chastity, and for continuing to offer guidance on how to do it.

Equip didn’t just help me stay in a biblically-rooted church—it helped me believe that true faithfulness and true love don’t have to be at odds. For that, I am deeply grateful.